On July 27, 2025 Phil Scott, Governor of Vermont, signed into law a cell phone ban affecting all Vermont schools. This ban was implemented because the Vermont legislature was concerned about Vermont students’ well being and education. This law will go into full effect by the 2026-2027 school year. However, Blue Mountain Union has decided to enact the law this school year. In order to help students follow this rule, the school has purchased the Yondr system, small pouches that lock digital devices with magnetic closures, for all 7th- 12th-grade students.

Since 2023, 27 states have enacted cell phone policies, including Vermont’s neighbors: New York and New Hampshire, and 4 states have a complete statewide restriction against cell phones: Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and Utah. Vermont’s restriction applies to public schools, approved independent schools, and career / technical education centers. When the BNN asked local senator Larry Hart, who represents the Orange District, what prompted the bill, he shared that “students from high schools. . . .came to the State House to ask for the ban because of [the] social media bullying that was happening.”

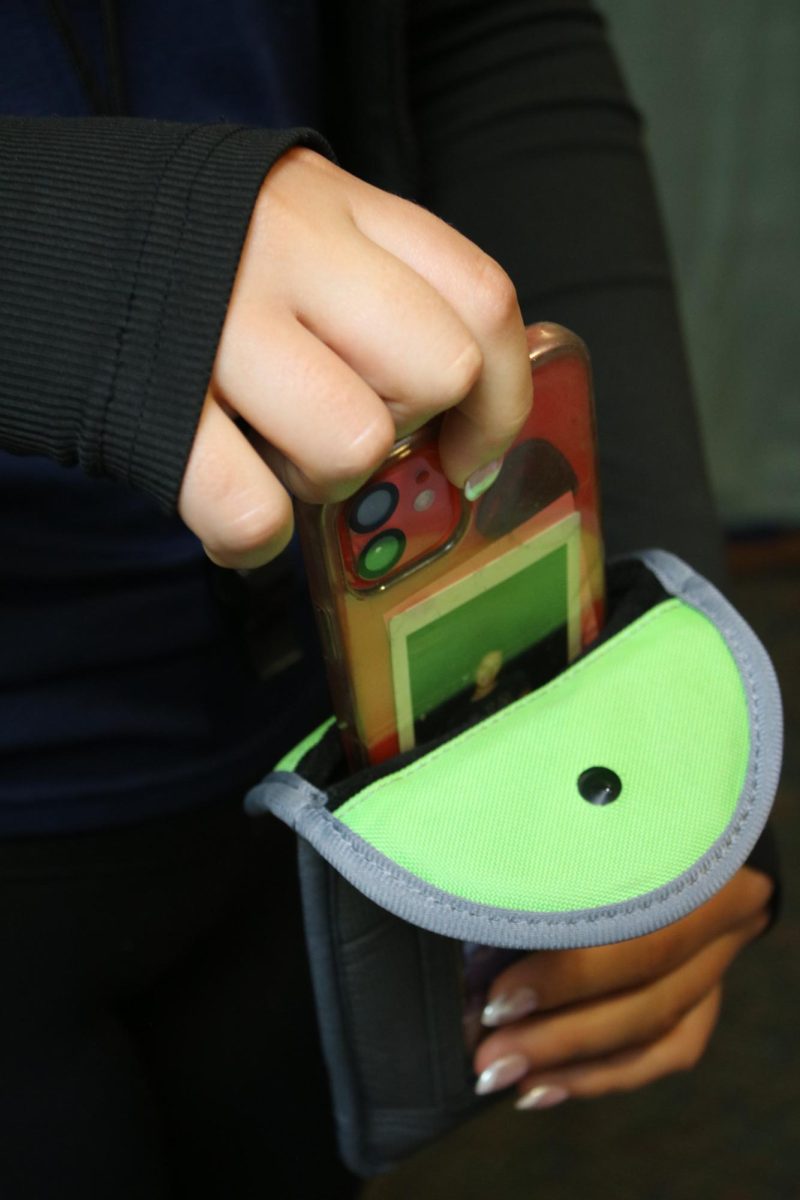

Despite the law going into effect in the 2026-2027 school year, BMU decided to enact it this year. The restriction extends to staff, who do not use their phones during classes unless they serve a specific academic purpose such as how to deposit a check using an app for a finance lesson. When asked why BMU decided to ban cell phones this year, Middle and High School Principal, Emilie Knisley, explained: “We decided to enact the phone policy earlier because we know that limiting phone use in school is better for the mental health of our students, as well as for the climate and culture of the school. We didn’t want to wait to take the step if we knew that making the change was going to improve the student experience at BMU.” To put the policy into practice, BMU invested in the Yondr system using money from the Curriculum Spending Budget.

Yondr, founded in 2014, is best known for its pouches designed to limit cellphone use at events and in schools. Originally created for concerts to help fans focus on the music, the pouches quickly caught the attention of musicians like Alicia Keys, Guns N’ Roses, and the Lumineers, who now use Yondr at their shows. The system was later introduced to schools across the U.S. as a way to reduce issues like cyberbullying and classroom distractions. Each pouch costs $25–$30, depending on the size of the district, and is now being used in several schools in New Hampshire and Vermont. In schools, the system requires students to place their phones into a magnetically locked pouch at the start of the day. The pouch stays locked until dismissal, ensuring that phones are not a distraction during classes, lunch, or passing time while still allowing students to keep their devices with them throughout the day. If a student leaves before 2:20, they need to go to the front office to get their pouch unlocked.

The administration’s choice to move ahead of the state mandate reflects a belief that limiting phone use now will strengthen both student learning and school culture. To understand why this step matters, it helps to look at how smartphones affect education, social connections, and emotional well-being.

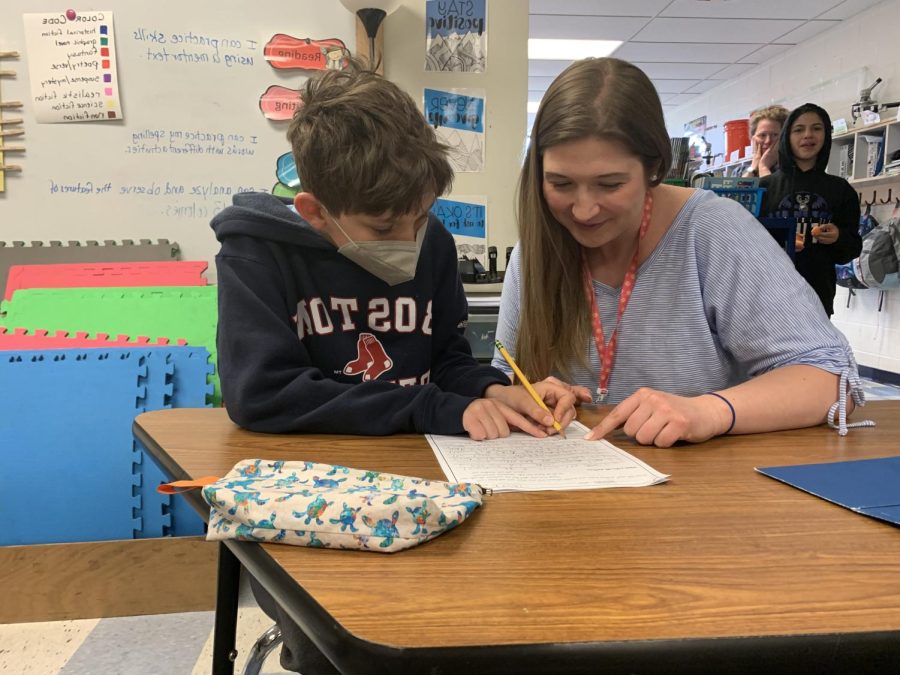

Smartphones can be helpful educational tools, offering interactive learning apps and resources. Social sciences teacher Nicole Hill noted that she never had issues with phones in her class; in fact, her students often used them to complete assignments by taking photos, making short films, scanning QR codes, producing podcasts, and gathering data. Similarly, many students say phones were critical to learning and focusing in their classes. In previous years, BMU students often relied on their phones for research, using them to look up quick facts, definitions, or background information for assignments. They also used learning tools such as: calculators, language apps, and quiz platforms like Quizlet or Kahoot; along with features for note-taking and organization: typing notes, snapping photos of whiteboards, checking calendars, Google Classroom, and setting reminders for homework due dates. In addition, phones supported creative and collaborative work–from recording videos or taking photos for assignments (notably for the BNN), to listening to books on audio, using talk-to-text for writing, and messaging classmates to share documents and coordinate group projects. BMU senior Kurtis Brooks added that another important learning tool used on cell phones was music apps like Spotify, Apple Music, and Amazon Music. He shared that without these,“It’s kind [of] hard to focus.…when I’m studying.” This sentiment is echoed by junior Paxton Hosmer who added that without his phone to assist in studying,”it’s hard to get used to.”

While many students feel that phones supported their learning, research proves they can also be major distractions from educational success. In fact, according to a 2025 study conducted by the U.S. National Center for Education Statistics, 53% of school leaders reported that cell phone use negatively impacts academic performance, and more recently, the National Report Card (NAEP) shows eighth graders’ science scores have fallen four points since 2019, and twelfth graders’ math and reading scores have fallen three points as well. One of the factors attributed to the decline in students’ test scores is cell phone usage.

Beyond the statistics, BMU students shared some troubling stories related to cell phones and academic issues. Perhaps most alarmingly, some BMU students reported that they began by using phones for school-related purposes but eventually found themselves relying on them for nearly every task, even replacing their own critical thinking. Admittedly, in our own newsroom, students shared that this reliance on technology concerns them. One reporter, Jamal Saibou, clarified that “students were using their phones to do literally everything,” which he felt hindered true learning.

Cell phones also play a complicated role in students’ social lives. On one hand, they offer opportunities to meet new people, make friends, and stay connected during the school day. On the other hand, removing phones can also bring clear benefits. Students report that not having a phone can ease pressure and allow them to focus more fully on class since they are not as worried about what might be happening outside of school. BMU junior Ava Kingsbury explained that before the ban, “if your friends were doing something outside of school and you saw it online, then you started to feel left out–especially in terms of the field trips. If people went on a trip and you didn’t go, then you started to feel like you should’ve gone.” This is no longer the case between 7:30 – 2:20.

Without the constant pull of social media, students are less likely to spend valuable class time scrolling. Research shows this matters: according to the American Psychological Association, teens now average about five hours a day on social media, and 41% of those who use it report their mental health as poor. U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy has also warned that “when adolescents spend more than three hours a day on social media, we are seeing a doubling of anxiety and depression.” BMU parent Clarissa Kendall echoed this concern, saying, “It’s important for everyone to get a break from social media.” Now with the phone ban in place, students have become more interactive with teachers and peers.

For many parents and educators, the bigger issue is how phones affect face-to-face relationships. Before the ban, it was common to see students sitting together but interacting with their screens instead of each other. Over time, this kind of ‘screen-first’ behavior can create a sense of isolation. The hope is that the new policy will push students to lean on one another instead of their devices. BMU parent Erin Nelson explained that if students are feeling isolated, they “might be more inclined to reach out to another student to get involved in practicing communication with each other.” High School English teacher Meghan Girrior has noticed a similar change, observing that “it almost seems that there is a relief” among her students, who are now socializing more and paying closer attention in class.

Still, going phone-free does not guarantee stronger connections amongst peers. Some students may choose not to socialize, regardless of a school cell phone policy. Others worry about feeling left out or about losing the ability to communicate with parents, friends, coaches, or teachers during the day.

However, the impact of smartphones extends further, affecting students’ emotional and psychological well-being. Studies link heavy smartphone use to anxiety, low self-esteem, loneliness, depression, and distorted self-image. Excessive use can even lead to irritability or addiction-like behavior. Senior Dylan LaCasse explained that since the cell phone ban took effect, he has noticed that he is “not really addicted to my phone anymore.”

At the same time, eliminating phones entirely raises another kind of anxiety: fear of being unable to reach loved ones in the event of an emergency. Nelson acknowledged this tension, noting that, “If it’s a true emergency, the school has systems in place to handle it. And, parents being notified through texts or calls can be comforting for the kids and that was my son’s concern…. Especially younger kids worry about school shootings, which is just unfortunate, but there are systems in place that are really going to be the most crucial thing in a situation like that.”

While safety concerns remain an important part of the conversation, daily classroom life around BMU has already begun to reflect the changes; with the phone ban in place, BMU students have become more interactive with teachers and with each other. Time will tell if Yondr pouches will decrease addiction, depression, cyberbullying, and help increase mental health, productivity, and human connection in students. But for now, students, paraeducators, teachers, and administrators have noticed the change. Mrs. Knisley notes that it is “a big shift,” and the school year has just begun, but she is “happy with it [the phone and Yondr policy] thus far.”

Carol wilber • Sep 13, 2025 at 9:53 pm

I believe. It’s a great idea they can look things up at home. School is for learning which we had to do with dictionary and encyclopedias! Homework assignments were giving and we did at homee!